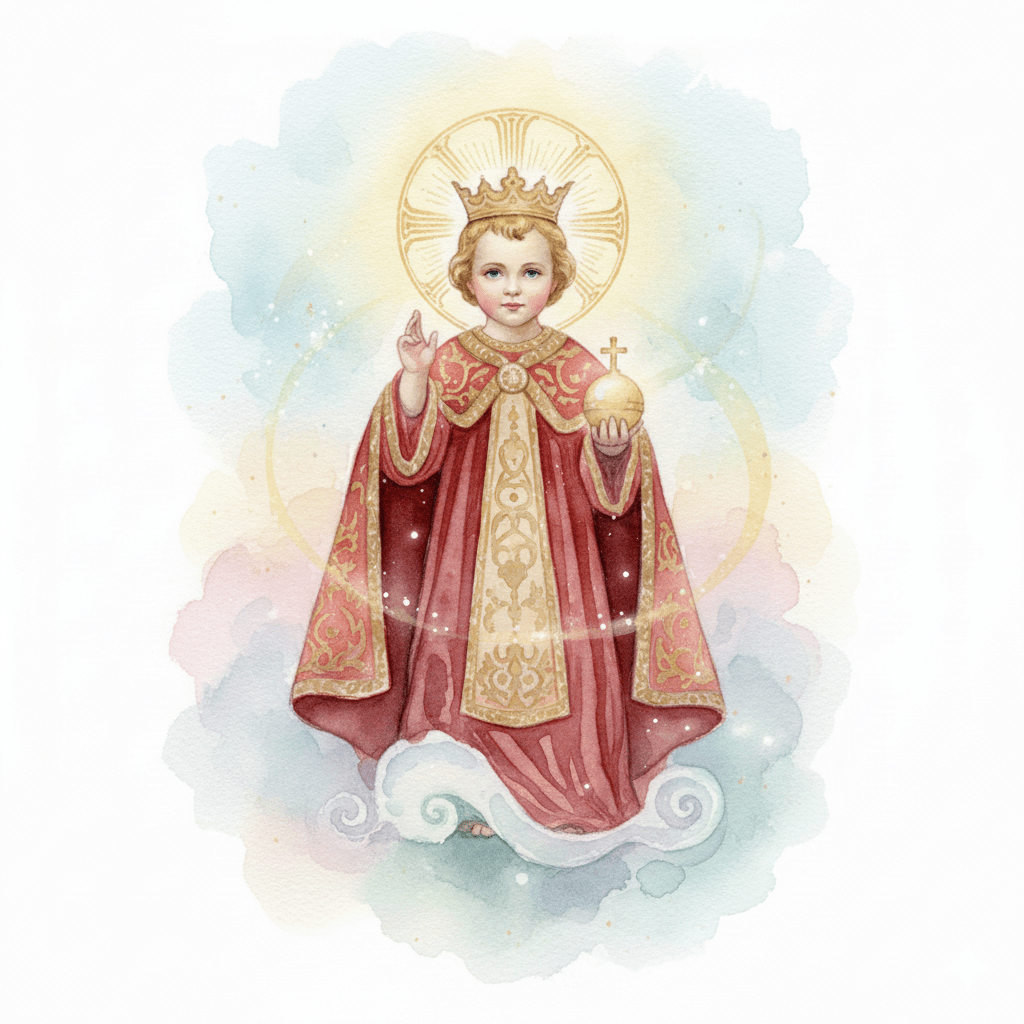

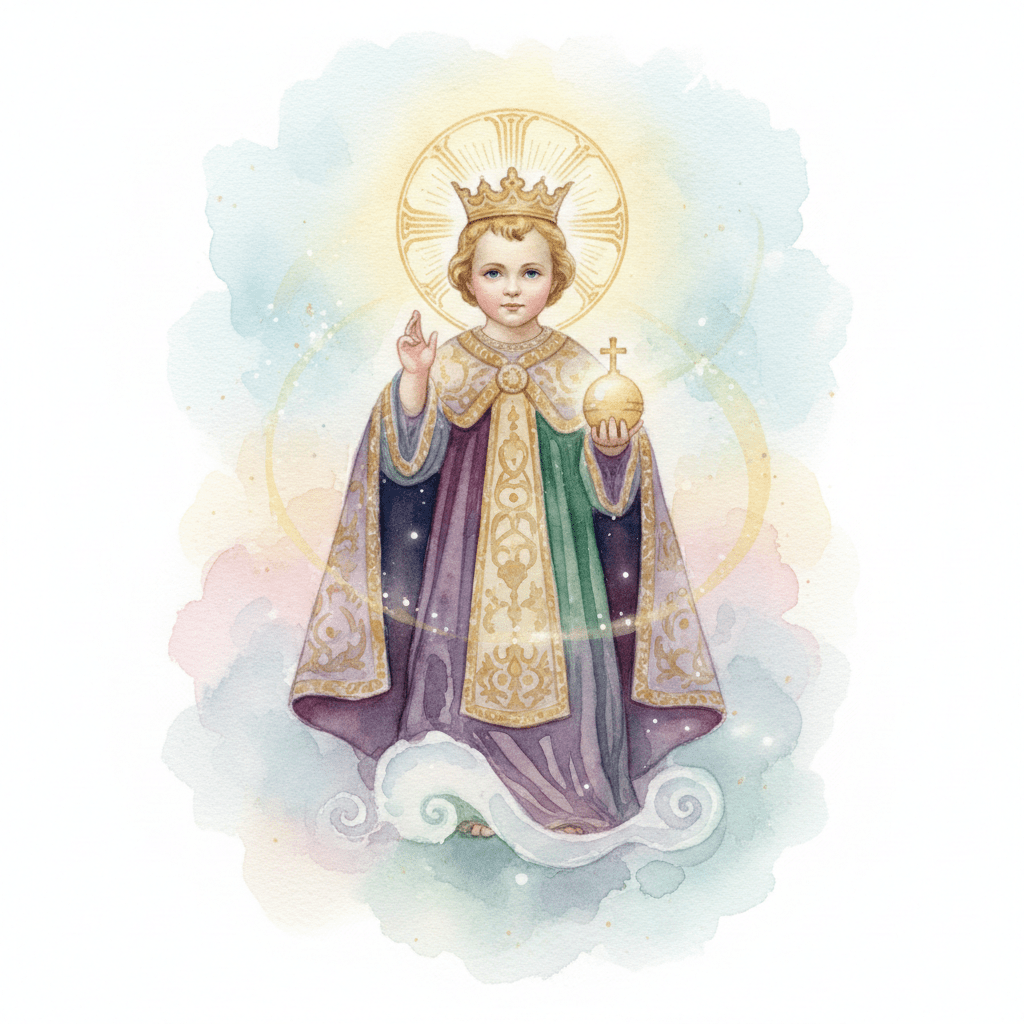

The Holy Infant Jesus of Prague, with his stiff brocade robes and golden orb, stands as a cornerstone of Carmelite devotion. Yet, to the student of comparative religion and depth psychology, this Little King is more than a 16th-century Spanish artefact. He is a manifestation of one of humanity’s most persistent and powerful psychic structures: the Divine Child. Long before the wax-coated figure was donated to the friars in Prague, the image of a small, vulnerable, yet cosmically powerful infant existed in the collective imagination of the ancient world.

The Puer Aeternus and the Mystery of Potential

At the heart of the Infant of Prague’s appeal is the concept of the Puer Aeternus, or the Eternal Boy. In Jungian psychology, this archetype represents the pre-conscious state of the human soul—the part of us that remains forever young, full of potential, and untouched by the cynicism of the adult world. The Infant of Prague embodies the paradox of this archetype: he is a child who requires our care (represented by the monks who dress and protect him), yet he holds the globus cruciger, the orb of the world, signifying that he is the one who sustains us.

This “Small-Great” paradox is a recurring theme in pagan antiquity. It reflects the mystery of the seed, which is tiny and fragile but contains within it the blueprint for a towering oak. When devotees look at the Infant, they are not just seeing a historical Jesus; they are looking at the personification of “The Beginning,” the divine spark that exists within the darkness of the material world.

Solar Rebirth and the Solstice Child

The timing and symbolism of the Infant are deeply intertwined with solar myths that predate Christianity by millennia. In the Northern Hemisphere, the birth of the Divine Child has almost always been celebrated at the Winter Solstice. This is the moment when the sun reaches its lowest point and the Light of the World is reborn.

The Infant of Prague is often depicted with a sunburst halo or a crown that radiates golden light. This imagery directly echoes the cult of Sol Invictus (The Unconquered Sun) and the Persian god Mithras, whose birth was celebrated on December 25th. In these traditions, the deity is born as a small child in a cave or a dark place—symbolising the womb of the earth—at the exact moment the days begin to lengthen. The Infant of Prague serves as a Christianised vessel for this ancient solar hope: that even in the dead of winter, the ‘New Light’ has been born to reclaim the throne of the year.

From Horus to Hermes: The Pre-Christian Pedigree

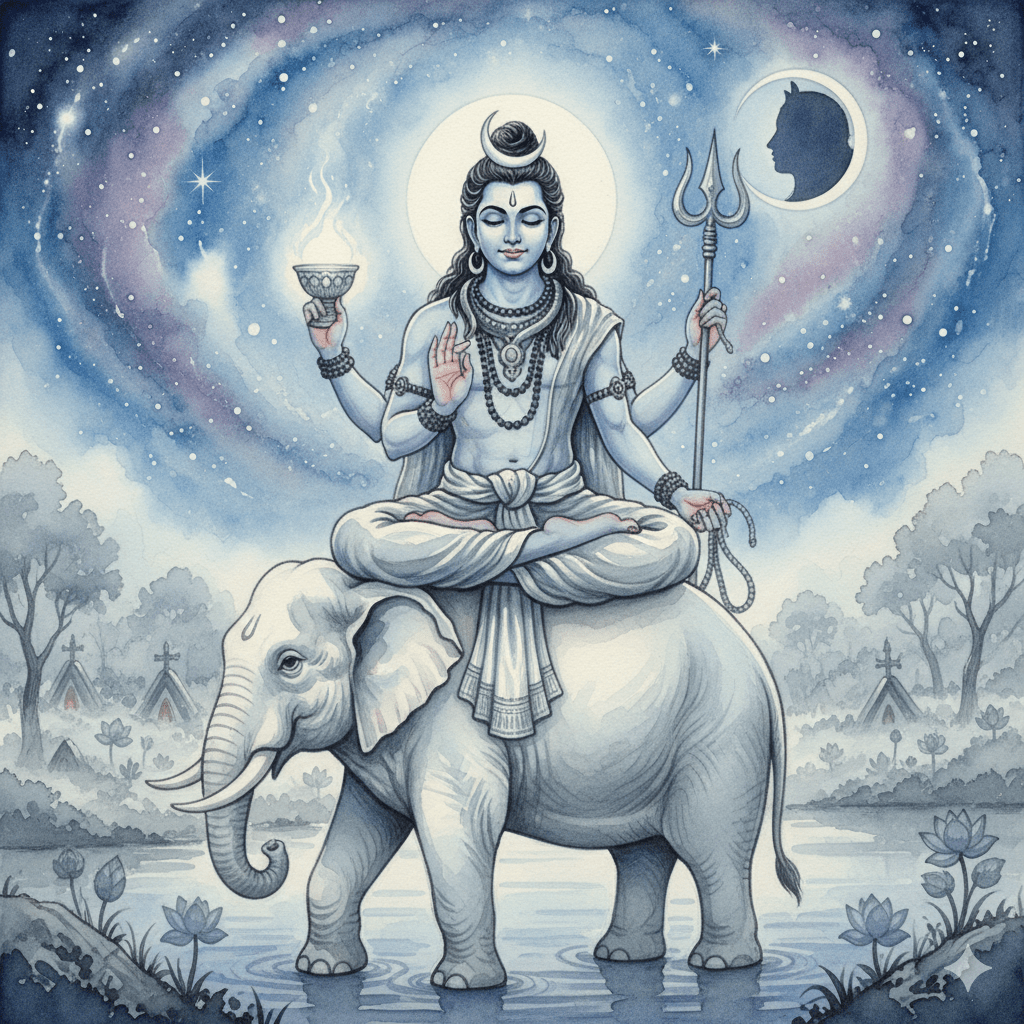

The visual and functional characteristics of the Infant of Prague find striking parallels in the pantheons of Egypt and Greece. Perhaps the most direct ancestor is the Egyptian god Horus the Younger (Harpocrates). Often depicted as a child with a finger to his lips or sitting on the lap of his mother, Isis, Horus represented the rising sun and the legitimate heir to the throne of the universe. The transition from the “Isis and Horus” iconography to the “Virgin and Child” is a well-documented path in art history, but the Infant of Prague takes this a step further by emphasising the child’s kingship, a central theme in the Horus myth.

Similarly, the Greek god Hermes was celebrated in his infancy as a “thieving,” precocious child who invented the lyre and stole the cattle of Apollo while still in his swaddling clothes. This reflects the “trickster” aspect of the Divine Child—a figure who breaks the rules of nature and logic. The Infant of Prague’s “miraculous” history, such as the legend of him speaking to Father Cyril and demanding his hands back, mirrors this ancient idea of the “Talking Infant” who possesses wisdom far beyond his years.

The Domestic Protector and the Lar Familiaris

Beyond the grand mythology of kings and suns, the way the Infant of Prague is used in modern Catholic homes has deep roots in Roman domestic religion. The Romans worshipped the Lares, household deities who protected the family and its prosperity. These were often depicted as youthful, dancing figures.

In many cultures, the Infant of Prague is kept specifically to ensure that the house shall never be in want. Devotees often place money under the statue or dress him in green to attract financial stability. This practice is a modern survival of “the cult of the household protector.” By bringing the “Little King” into the domestic sphere, the practitioner is recreating an ancient sacred space where the divine is not a distant, terrifying judge, but a small, familiar presence that guards the hearth and the pantry.

Conclusion: The Child as the Final Goal

Ultimately, the pre-Christian roots of the Infant of Prague do not diminish his Christian significance; rather, they reveal why he resonates so deeply with the human heart. He is the “Alpha and Omega” in a literal sense—the God who becomes the smallest of things to make the largest of changes. By tapping into the ancient archetypes of the Solar Child, the Royal Heir, and the Household Protector, the devotion to the Infant of Prague connects the modern believer to a primordial lineage of human spirituality that has always seen the Divine as a child, waiting to be born within the soul.

Leave a comment