The crucifix–a figure both divine and human suspended upon the cross–stands as one of the most powerful and paradoxical symbols in human culture. While its origin is rooted in Christian narrative, the significance of the iconography transcends religious boundaries, inviting reflection on the nature of imagery, representation, and the tension between visibility and invisibility.

Beyond its Christian context, the crucifix has evolved into a symbol layered with meanings that resonate across cultures and disciplines. In art, literature, and social discourse, it surfaces as a metaphor for sacrifice, injustice, endurance, and redemption-and not only in religious terms, but as archetypal motifs.

To understand the crucifix is to engage with a symbol that embodies both presence and absence, embodiment and transcendence, suffering and healing, death and resurrection. Its power, perhaps, lies in its ambiguity and openness to interpretation. The crucifix is simultaneously a historical artefact, a theological statement, and a universal icon of human experience. It invites viewers to confront discomfort, to meditate on paradox, and to explore the limits of representation.

The Crucifix as an Iconographic Enigma

At first glance, the crucifix appears to be a straightforward depiction of a historical event: a man executed by crucifixion. Yet, as an icon, it functions on multiple levels simultaneously. The image is not merely illustrative; it is performative and contemplative. Each element–the outstretched arms, the vertical and horizontal beams, the figure’s posture–operates within a visual language that conveys theological, philosophical, and existential themes.

In its most literal sense, the image references a specific moment in history–that of an individual affixed to a wooden cross, exposed to public view, and subjected to a slow, excruciating death. This method of execution was intentionally designed to be both physically torturous and symbolically degrading.

The condemned was often stripped, scourged, and forced to carry the crossbeam through the city streets, transforming the act into a public spectacle. The cross itself became an instrument of both suffering and social warning. The victim’s body, suspended between earth and sky, was left to die over hours or days, serving as a grim reminder of the power of the state and the consequences of defiance.

Within the context of iconography, the crucifix thus operates on two levels. On the surface, it is a visual record of a real, historical practice. Yet, as the image was adopted and adapted by artists and communities, it became layered with additional meanings: the body on the cross transformed from an anonymous victim of imperial violence into a symbol of sacrifice, endurance, and, paradoxically, faith.

This transformation is precisely what made the crucifix so contentious during periods of iconoclasm. For some, the image’s raw depiction of suffering was too visceral, its materiality too bound to the world of flesh and pain. For others, the very act of representing such a moment in visual form was an essential means of engaging with the mysteries of existence and transcendence. Thus, the crucifix stands as both a historical document and a symbolic threshold: a visual site where the realities of history and the aspirations of meaning intersect.

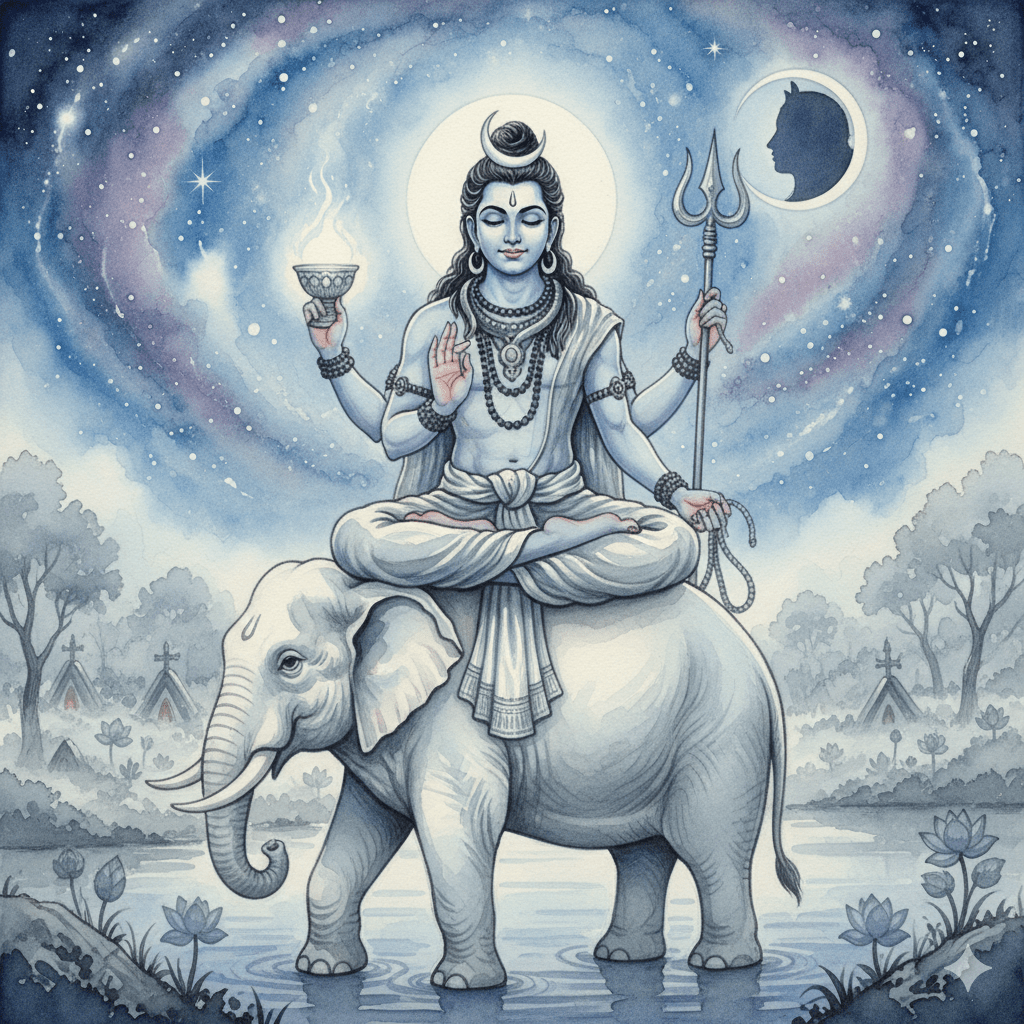

The crucifix can be read as a spatial and temporal nexus: a point where the earthly and the divine intersect and where time seems to pause. Its form echoes ancient symbols of the cosmic axis, the axis mundi, connecting realms above and below. The figure on the cross becomes a liminal presence, embodying the paradox of suffering as a gateway to transcendence.

Iconoclasm: The Ambivalence Toward the Image

The history of the crucifix is inseparable from the history of iconoclasm: the deliberate destruction or rejection of religious images. This phenomenon reveals a profound ambivalence toward the power of images themselves. Iconoclasts challenged the legitimacy of the crucifix as a representation, fearing that the sacred would be reduced to an object and that the image would eclipse the reality it sought to represent.

This anxiety exposes a fundamental philosophical tension: can the infinite be captured in finite form? Is the image a bridge to the sacred or a barrier? The crucifix, with its visceral portrayal of human vulnerability and divine mystery, became a focal point for these questions. Iconoclasm was not just a theological dispute, but a cultural struggle over how humans relate to the visible world and the unseen realities it gestures toward.

In most ancient and classical art, the human form was depicted in moments of power, beauty, or serene transcendence. Gods and heroes were shown victorious, kings enthroned, philosophers in calm contemplation. The crucifix, by contrast, is an image of utter vulnerability and loss. It is not a sanitised or heroic death, but a moment of abandonment, humiliation, and pain.

For a spiritually curious, not necessarily religious viewer, the crucifix is not simply a scene or a symbol. It is a visual rupture. In the history of art and iconography, it stands out as an image that should not exist: the execution of a single, recognisable individual, rendered not in triumph or idealised beauty, but in the midst of agony, defeat, and exposure.

This is not just unusual. It is radical. The crucifix refuses to flatter, refuses to comfort, and refuses to conform to the expectations of what a ‘sacred’ image should be. It is, in a sense, an anti-icon: an image that draws its power from the very things that polite society and classical aesthetics would rather look away from.

What makes the crucifix so striking is its insistence on the particular: this body, this suffering, this moment. It is not a metaphor, not a myth, not an allegory. The image demands that the viewer confront the reality of what is depicted. It is a challenge to the viewer’s gaze-a test of empathy, discomfort, and attention.

For the spiritual viewer, the crucifix can function as a kind of koan-a visual paradox that cannot be solved or explained away. Why depict this? Why insist on showing what is usually hidden? What does it mean to make the site of execution and humiliation into the focal point of contemplation and artistic devotion?

An Invitation

The crucifix, then, is a provocation that asks the viewer to grapple with the unacceptable, the unredeemed, the unresolved. It is a visual space where meaning is not handed down but must be wrestled with. For those who are spiritually open, but not religious, this is where the crucifix becomes fascinating: not as a symbol of doctrine, but as an invitation to radical presence.

It asks: Can you stay with what is difficult? Can you witness what is uncomfortable? Can you find meaning-not by escaping the image, but by letting it work on you, unsettle you, and perhaps even transform your way of seeing?

The crucifix is a threshold-an invitation to engage with the profound complexities of symbol, image, and meaning. It challenges viewers to hold paradoxes in tension: suffering and hope, presence and absence, form and formlessness. As an icon and as a contested object, the crucifix reveals the enduring human struggle to articulate the ineffable through the visible, to find meaning at the intersection of the material and the transcendent.

The Wounded Healer

For readers seeking a profound meditation on healing, my work of prose-poetry Oneness offers a luminous journey through the valleys of love, longing, heartbreak, and renewal. The book draws from Hindu mysticism, biblical wisdom, and Christian contemplation to explore the delicate rhythms of human connection and the fragile territory of the heart. Through the intertwining of two souls across lifetimes, my work reveals how our deepest wounds and desires are both the source of our struggles as well as the wellspring of our healing.

Oneness invites readers to reflect on the cycles of struggle and happiness, solitude and intimacy, and to recognise that healing arises from embracing both our vulnerabilities and our connections with others. By transcending religious dogma and weaving together diverse spiritual traditions, I hope to offer a compassionate and universal vision of healing that speaks directly to the soul. Oneness is available at all major online bookstores and at Singapore’s National Library Board (NLB) libraries, making it accessible to anyone seeking solace, insight, and the courage to heal.

Leave a reply to A Radical Invitation | Jesus the Saviour Who Heals Our Wounds – the mercantile. Cancel reply