The widespread portrayal of ancient societies as lands dominated by primitive goddess worship and idolatry may reflect less about historical reality and more about the political needs of later historiography. Recent scholarship suggests that the emphasis on polytheism—particularly the veneration of goddesses—was amplified in later sources to create a stark contrast between a supposed “Age of Ignorance” and subsequent monotheistic reforms.

Early texts from emerging monotheistic traditions systematically depicted earlier societies as chaotic and morally bankrupt. This served to legitimise the new religion’s emergence as a civilising force, often justifying the destruction of pagan shrines and temples, thereby reinforcing the theological premise of divine unity by exaggerating earlier polytheism.

Scholars note that writers often framed earlier history through their own religious lens, selectively memorialising practices like idol worship to construct a “before-and-after” narrative. While goddess worship existed, its scale and cultural significance appear overstated.

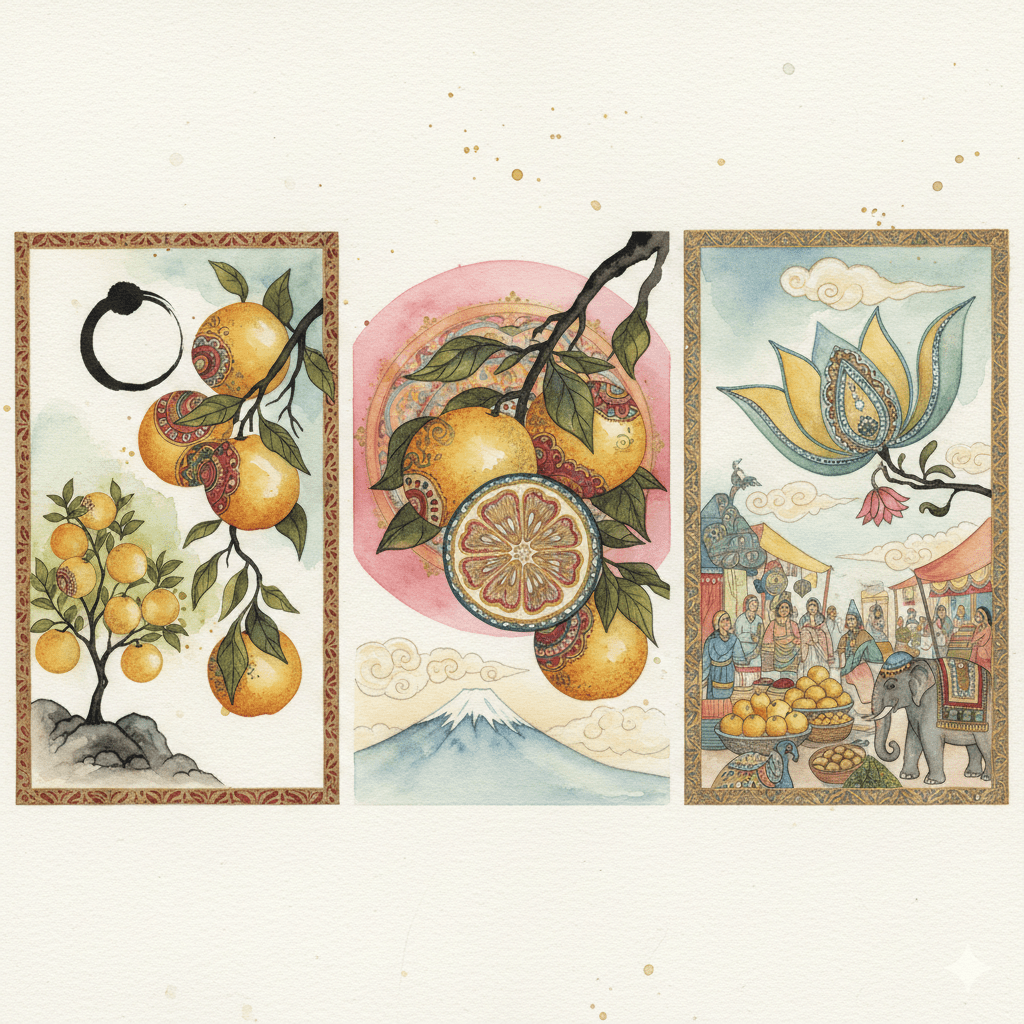

Goddess Worship

Archaeological evidence shows limited organised cults for certain goddesses compared to what later accounts suggest. Cultural influences often blended local deities with those of other traditions, reflecting cultural exchange rather than deep-rooted paganism. Reports of numerous idols may symbolise ritual completeness rather than literal practice.

Goddess figures often became rhetorical foils in monotheistic theology. Sacred texts explicitly reject these goddesses as false intermediaries, framing them as tests of monotheistic loyalty. Emphasising certain tribes’ devotion to specific goddesses helped marginalise rival groups during religious consolidation. While goddesses were superficially powerful, their demotion in later polemics reinforced patriarchal monotheism.

Ancient societies were far more religiously diverse than the pagan-vs.-monotheist binary suggests. Various religious communities often coexisted in the same regions, and monotheistic movements even predated the major organised religions we know today. Labels like “Age of Ignorance” often conflated tribal violence with religious practice, obscuring complex social realities.

This narrative construction has enduring consequences. It shapes perceptions of cultural identity, divorcing ancient cultures from their multicultural context. Feminist reinterpretations further challenge the assumption that goddess worship equated to female empowerment, noting that mortal women’s status remained constrained even in goddess-venerating societies.

The portrayal of ancient goddess worship as a primitive foil for later monotheistic traditions reveals more about the political and theological imperatives of later historians than about antiquity itself. By critically reevaluating sources—both textual and archaeological—we uncover societies in transition, where various religious currents and tribal pragmatism coexisted long before major religious reforms.

Leave a comment