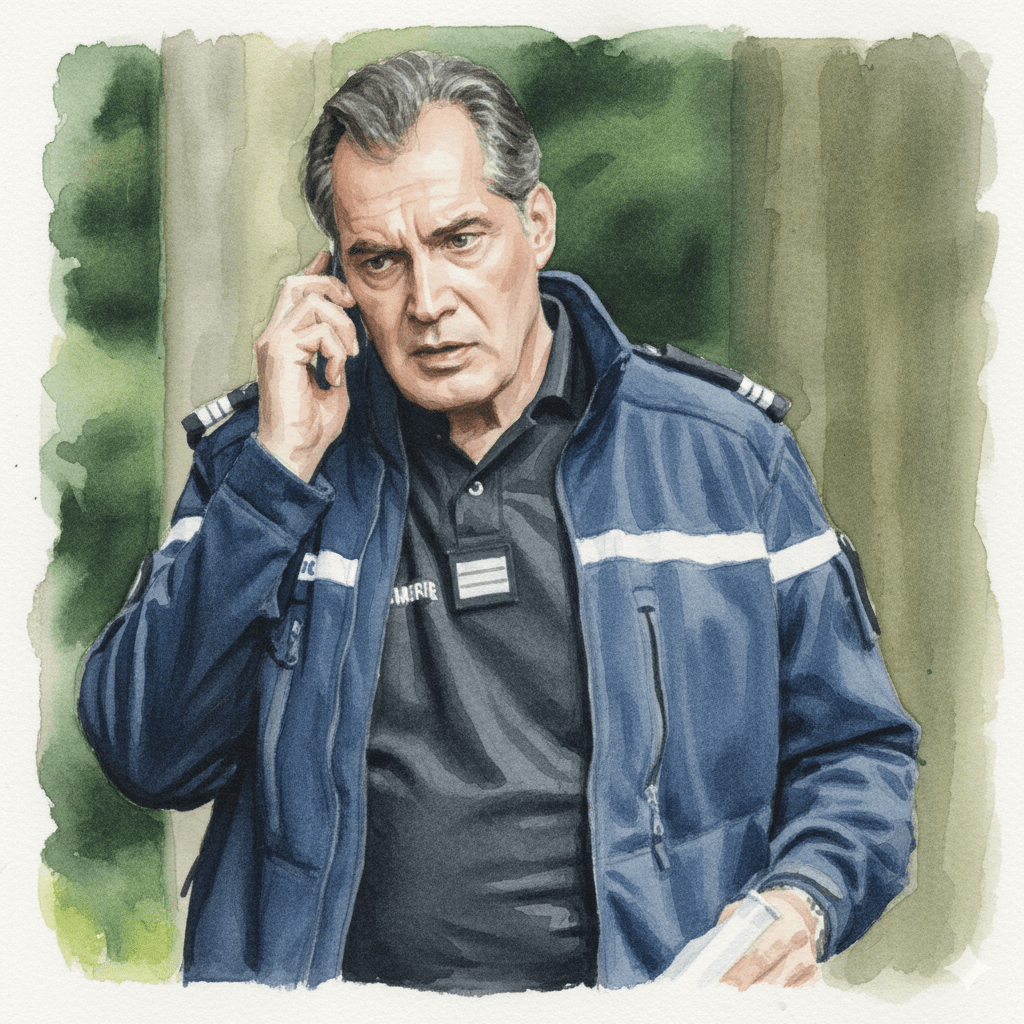

There is a kind of authority that does not ask for permission. It does not arrive through rank, through volume, or through the approval of those around it. It simply is — quiet, heavy, and self-sufficient. Gaspard Decker, the investigating captain at the heart of the French crime drama La Forêt (2017), is a man possessed of exactly this quality. He does not command the room because anyone gives him the right to. He commands it because something in his bearing makes resistance feel beside the point.

This quality has a name in the older traditions of character and temperament: it is Saturnian. Named for the planet long associated with lead, with slowness, with melancholy, and with time itself, the Saturnian archetype describes a particular kind of figure — one who carries an inner gravity that weighs on everything around them, who operates on a longer timescale than others, and who maintains order not through force but through an almost geological patience. Decker, played with exceptional restraint by Samuel Labarthe, is one of the more compelling Saturnian figures in recent European crime drama.

Authority Without Mandate

One of the most striking things about Decker is that the world of La Forêt does not make it easy for him to be in charge. He arrives in Montfaucon newly posted, unfamiliar to his colleagues, and without the social capital that long tenure in a place tends to accumulate. The local gendarmerie has its own rhythms, its own loyalties, its own skepticism toward an outsider stepping into their investigation. By any conventional measure, he has not earned authority here.

And yet he leads. Not because he demands it, but because he makes it difficult to imagine anyone else doing it. There is no swagger in Decker, no performance of dominance. His authority expresses itself through composure — through the sense that he has already considered what others are still reacting to, that he is operating several moves ahead without needing to announce it. People fall into step behind him not because they are told to, but because his gravity is simply stronger than theirs.

This is the Saturnian mode of leadership: not charisma, not force, but weight. Saturn does not pull planets toward it through charm. It does so through mass, through an inescapable field of influence. Decker’s leadership operates the same way. It is structural rather than performative, and it makes him both indispensable and, at times, quietly alienating to those around him — because authority that cannot be explained is also authority that cannot easily be argued with.

The Melancholy Beneath the Poise

Saturnian figures carry something heavy inside them, and Decker is no exception. His poise is not the poise of a man unburdened — it is the poise of a man who has learned to carry his burdens without letting them show. His personal history, revealed in fragments across the series, is one of loss and fracture: a past that has not been resolved so much as contained, pressed down beneath the surface of his professionalism.

This is the paradox at the heart of the Saturnian archetype. The same inner heaviness that makes these figures seem burdened also makes them reliable. They have already been through the worst of themselves. They are not surprised by darkness, not destabilised by it, because they have made a kind of peace with the fact that darkness exists — in the world, and in themselves. When Decker looks at the chaos of a missing girl, a panicked village, a team on the edge of losing cohesion, he does not flinch. Not because he is unfeeling, but because he has felt enough to know that flinching does not help.

There is a melancholy to his scenes that is hard to locate in any single moment — it is ambient, atmospheric, like a low-frequency hum beneath everything he does. It is present in the pauses before he speaks, in the way he absorbs information without immediately reacting to it, in the particular quality of stillness he carries even when things around him are moving fast. Samuel Labarthe renders this beautifully, never tipping into self-pity or heaviness for its own sake. It is simply there, an undertone, a reminder that the man doing this work has reasons to do it that go beyond the professional.

Patience as Method and Temperament

Where other investigators in the Montfaucon case react — to new evidence, to provocations, to the emotional weather of the community — Decker absorbs. He is a slow processor in the best possible sense: not slow to understand, but slow to conclude, holding possibilities open longer than is comfortable, refusing to collapse ambiguity into certainty before the evidence demands it.

This patience is both temperamental and methodological. Temperamentally, it speaks to a character who does not need immediate resolution, who can sit with uncertainty without it destabilizing him.

Methodologically, it is what makes him effective. The truth of what happened to Jennifer Lenoir is not something that can be rushed out of the forest. It requires time, accumulation, a willingness to let the case breathe. Decker gives it that time. He understands, at some deep level, that justice — real justice, not just closure — moves slowly.

This is Saturn’s domain: time. The planet was historically associated with old age, with harvest (the long wait between planting and reaping), with the slow accumulation of consequence. Decker investigates the way Saturn governs — not in bursts of inspiration but in steady, methodical pressure. He is the figure who is still there when others have given up or moved on, still asking the question that has not yet been answered, still holding the thread.

Holding the Line: Order in a Disintegrating World

Around Decker, La Forêt stages a community in the process of coming apart. The disappearance of Jennifer — and later Maya — does not just generate grief; it generates fracture. Old tensions surface. Neighbours turn on one another. The forest, ancient and indifferent, seems to amplify the sense that the social order of Montfaucon was always more fragile than anyone admitted.

Decker does not save this community from its fractures. That is not his role. But he maintains, within the investigation itself, a disciplined order that prevents the search for truth from becoming merely another form of chaos. He draws lines. He insists on process when others want to skip to conclusion. He absorbs the emotional turbulence of his colleagues — Virginie Musso’s terror, the community’s pressure, the institutional friction of the gendarmerie — and converts it, quietly, into forward motion.

This is the Saturnian function in any system: to be the structural element that holds when everything else is threatening to give. Not warmth, not inspiration, but structure. A frame that keeps the picture from falling apart. Decker is that frame in La Forêt, and the series is careful to show how costly it is to be that — how much it takes from a person to be the one who does not get to fall apart.

Conclusion

Gaspard Decker is not a comfortable character. He does not invite easy affection or simple admiration. He is too still for that, too interior, too marked by something the series only partially reveals. But he is a deeply compelling one, precisely because the archetype he inhabits is so rarely rendered with this much fidelity and care.

The Saturnian figure — melancholic, patient, authoritative without seeking authority, order-keeping in a disordering world — is ancient. It appears in literature, in mythology, in the long tradition of characters who carry weight so others do not have to. In La Forêt, Gaspard Decker inherits that tradition and makes it contemporary, makes it specific, makes it human. He moves through the dark Ardennes landscape like a man who has already accepted that the world is heavy, and who has decided, despite that — or perhaps because of it — to keep going anyway.

That is Saturn’s gift and Saturn’s burden. Decker carries both.

Leave a comment