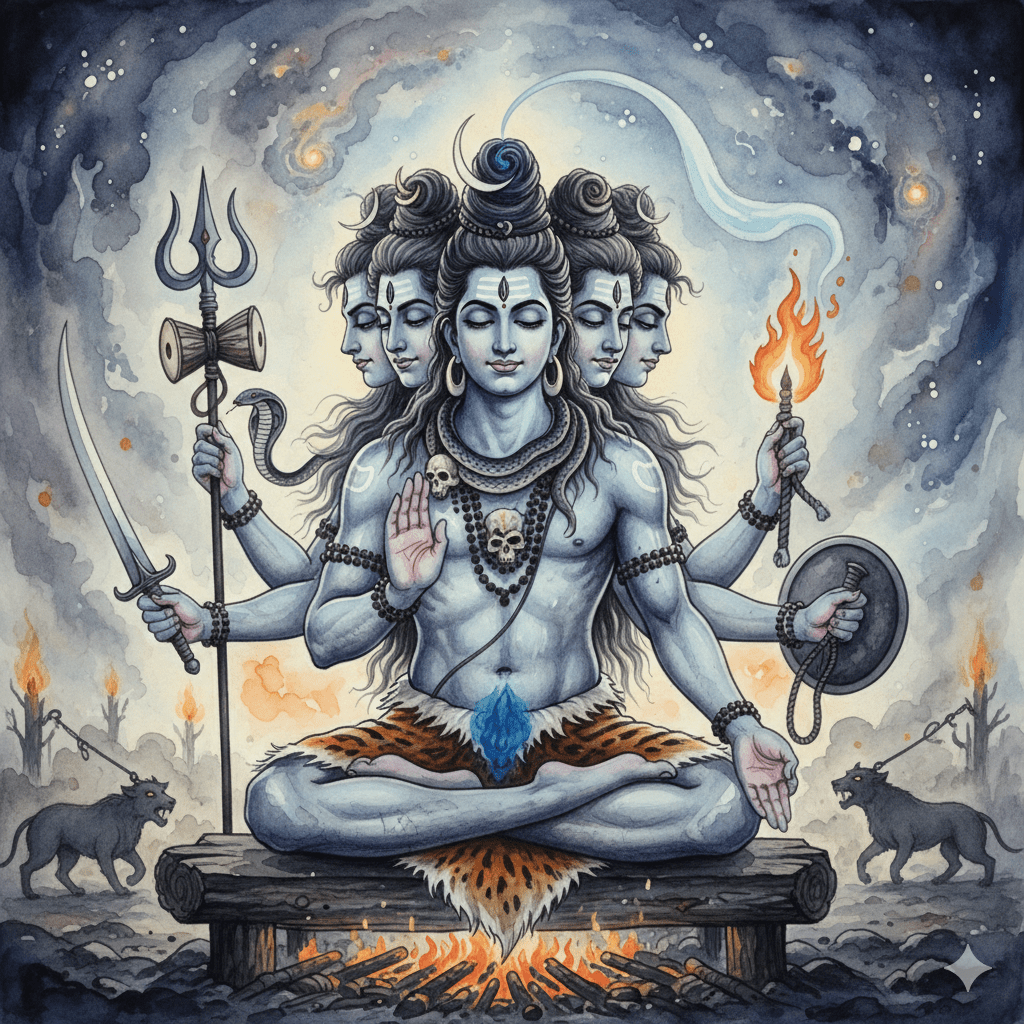

In the vast landscape of Hindu belief, while many deities offer protection, blessings, and guidance, it is Shiva—Mahadeva, the Great God—who is singularly cast as the ultimate liberator. His name and form are inseparable from the idea of freedom: freedom from suffering, from the cycles of life and death, and most crucially, from the invisible yet inescapable cords of karma pāsha.

Shiva is invoked as Pashupati, the Lord of all creatures, but in the deepest sense, this epithet marks his sovereignty over bondage itself. The word pāsha means “bond” or “noose,” referring not just to physical fetters but to the subtle entanglements of karma accumulated across lifetimes. These are not just actions, but the residues of desire, fear, regret, and unrest that compel the soul to return again and again to worldly existence.

The End of Karma

In the Shaivite vision—echoed throughout broader Hindu tradition—no other divine power is believed able to cut these cords. Vishnu, for instance, restores balance and preserves order, Brahma initiates creation, but neither claims nor is ascribed the unique office of dispensing with karma’s deepest roots. It is Shiva alone who, by nature and scriptural mandate, unties what binds.

This liberating power is illustrated through Shiva’s stories. Take the episode of Kamadeva, the Lord of Desire, who attempted to rouse Shiva from meditation. Shiva, with a mere glance, incinerated Kama, demonstrating not just control over individual passions, but the power to annihilate that which binds beings to the chain of cause and effect.

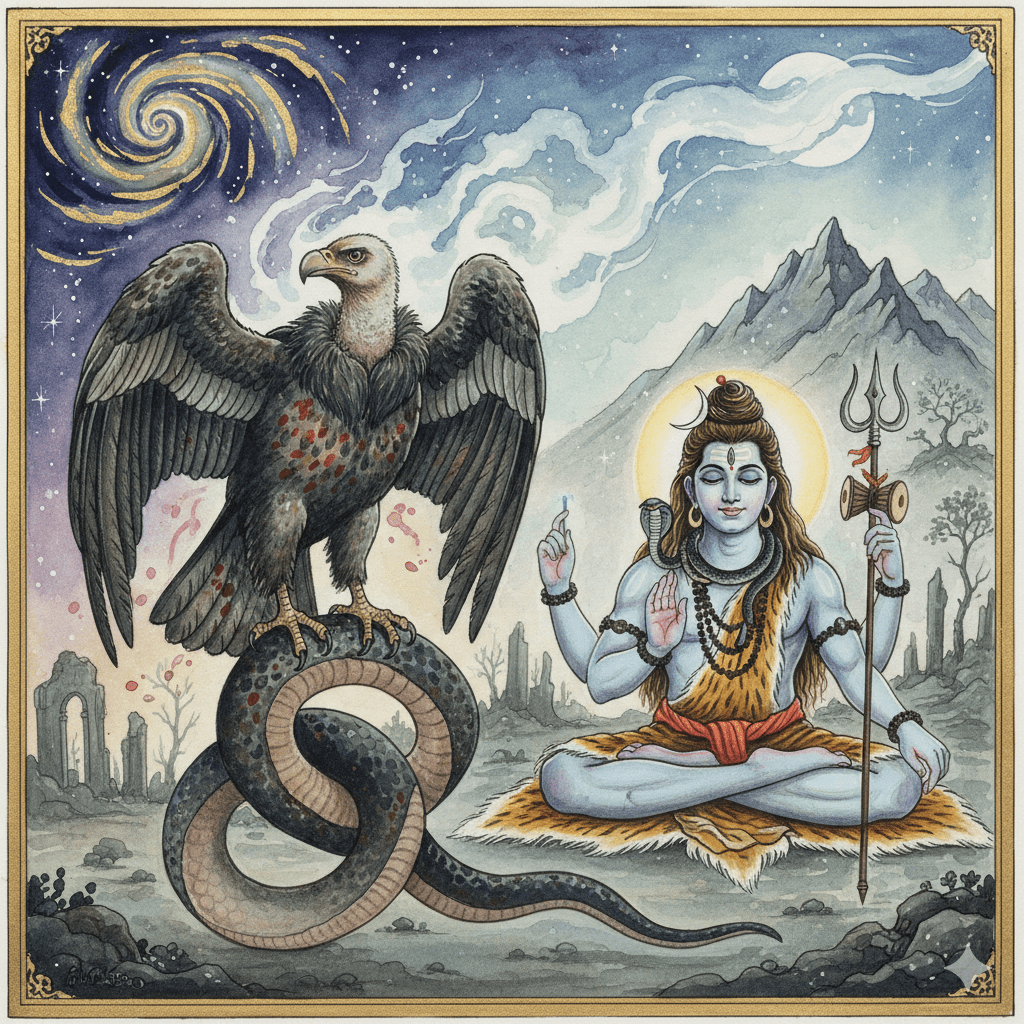

Even more evocative is the legend of the Samudra Manthan, the churning of the cosmic ocean. In this story, when a deadly venom—the halāhala—emerges, threatening the cosmos, it is Shiva who drinks it, containing and neutralising the poison in his own throat. This act is not only a tale of cosmic sacrifice, but a metaphor for Shiva’s unique role: accepting and transmuting the negative residues that no one else dares approach, saving the world from consequences it cannot resolve alone.

The Theology of Shaivism

This theological understanding directly informs Hindu ritual and remedial practice. Particularly when devotees confront afflictions believed to be rooted in dense, unyielding karma—such as those typified by astrological doshas like the Kaal Sarp, which is deeply intertwined with serpentine and poisonous symbolism—the traditions turn unambiguously to Shiva.

It is widely held that the obstacles marked by such doshas have their origin in lifetimes’ worth of unresolved actions and debts, symbolised by the entwining of Rahu and Ketu, and that only Shiva, with his reputation for mercy and transcendence, can unravel these entwined destinies.

The Shiva Purana and the Agamas are rich with injunctions and narratives affirming Shiva’s willingness and capacity to “burn up” even the most obstinate karma—whether through ritual worship (puja), the power of his mantras, or the transformative fire of austerity (tapas).

Devotees seek Shiva not simply for relief from immediate suffering but for a chance at final release, for moksha, the cessation of all future births (see Kingfisher). Worship of Shiva is therefore not just an appeal for problem-solving, but a quest for the deepest possible freedom: the soul’s return to its own luminous, unconditioned essence.

Across India and the global Hindu diaspora, this expectation shapes devotional life. Remedial rituals, pilgrimages to Jyotirlingas, the observance of austerities on Mondays and Saturdays, and countless acts of private prayer are all, implicitly or explicitly, directed by this confidence: that Shiva alone can untie the oldest, hardest knots of fate and allow the seeker to step, at last, beyond the cycle of becoming and unbecoming.

His mercy, said to be boundless, is the hope of the burdened soul. In this vision, Shiva remains eternally present, with hand outstretched, to liberate those who turn to him—not simply from their most visible troubles, but from the very bondage that defines human existence.

Leave a comment