Across cultures and centuries, the figure of a saviour appears in our myths, legends, and collective imagination. The saviour is the one who steps into chaos, confronts what threatens the community, and offers a way out-a bridge from despair to hope, from destruction to renewal. This archetype is not just a religious construct; it is deeply embedded in the human psyche.

The figure of Jesus has captured imaginations for centuries, not just because of what he did for humanity, but because of why he did it. The question of why Jesus tries to save people is not only central to his story, but it also invites anyone–regardless of belief or background–to consider what it means to be valued, to be sought after, and to be offered the help one needs to reach their goals.

Abandonment is a wound that cuts deeply. It is the result of fear, shame or prejudice within the community. It is about maintaining a sense of order or comfort by excluding those who seem too different, too troubled, or too inconvenient. At times, it is simply the cold consequence of indifference. Throughout history, and still today, individuals who do not fit the mould are often pushed to the margins, their suffering rendered invisible, their voices silenced.

From the outset, Jesus’ mission is described as a search-and-rescue operation. He states plainly that he ‘came to seek and to save the lost’. This is not a passive hope that people will find their way, but an active pursuit of those who have been overlooked, broken, or written off by society. The ‘lost’ are not just those who have made mistakes, but anyone who finds themselves cut off–by circumstances, by their own actions, or by the judgment of others.

This mission is rooted in a deep awareness of the human condition. People live with all manner of poverty, need, and estrangement-not just material, but emotional, relational, and spiritual. The stories about Jesus consistently show him moving toward those who are suffering, marginalised, or even hostile. He does not wait for people to become worthy of help; he goes to them where they are.

The Incarnation of God

The first theological argument is the incarnation itself. According to the earliest Christian texts, Jesus is the embodiment of the divine entering into human reality. This is not for spectacle or moral example, but because, as the Gospel of John puts it, ‘the Word became flesh and dwelt among us’. The logic here is that rescue requires presence.

Salvation, in this vision, is not an external intervention, but an inner participation in the very condition that needs healing. Jesus saves because, in this theology, God’s nature is not to remain aloof from suffering, but instead, to enter it fully.

The cross is the theological centre of why Jesus saves. The ancient world saw crucifixion as the ultimate shame and defeat. Jesus, however, undergoes abandonment and death not as a victim of fate, but as a willing participant in the world’s pain… and in its restoration. The argument, developed by the early church fathers, is that only by entering the deepest alienation can reconciliation be achieved. Jesus saves by absorbing the consequences of human and cosmic brokenness, not bypassing them.

The need for a saviour arises from the recognition of human limitation. Every society, and every individual, eventually faces forces too great to overcome alone: natural disasters, injustice, mortality and inner darkness. The archetype of the saviour emerges as a response to this existential vulnerability. It is the hope that, when all else fails, someone will come-someone with the courage, wisdom, or power to do what we cannot.

This figure is not always divine. Sometimes it’s a king, a hero, a prophet, or even an ordinary person who rises to the occasion. But the pattern is consistent: the saviour enters into the crisis, confronts the threat, and, often at great personal cost, brings about deliverance.

Alexey Akindinov, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

When we turn to the figure of Jesus, we find both continuity and disruption of the archetype. On one hand, Jesus fits the pattern: he enters a world in crisis, confronts evil, and offers rescue. But the way he fulfils the archetype is radically different from what most stories imagine.

Instead of wielding political or military power, Jesus embodies vulnerability. Instead of conquering through force, he absorbs violence and injustice. Instead of saving only the worthy, he seeks out those deemed unworthy, lost, or broken. His ‘victory’ comes not through domination, but through self-giving love, even to the point of death.

Greater love has no one than this, than to lay down one’s life for his friends. (John 15:13)

This is a profound reimagining of what it means to save. True rescue is not about escape from suffering, but the transformation of suffering itself. The saviour does not stand apart from the pain of the world, but enters it fully, refusing to abandon even those who have abandoned themselves.

The archetype persists because the need persists. We are still confronted by problems too big for us-personal, social, existential. The figure of the saviour, especially as exemplified by Jesus, asks us to consider: What kind of rescue do we really need? What does it mean to be saved-not just from danger, but from meaninglessness, isolation, or despair?

And perhaps most unsettling: are we willing to recognise the saviour not as a distant hero, but as one who comes close, who shares our pain, and who calls us to a deeper kind of transformation? When we see the saviour not as a remote, untouchable figure but as one who walks among us, the story shifts from mere admiration to profound invitation.

Jesus does not simply rescue from afar. He enters into the messiness of human life-its sorrow, doubt, and even failure. His solidarity with human suffering challenges us to reconsider what true salvation means. It is not just deliverance from hardship, but the promise that we are not alone in our struggles. In embracing our pain, the saviour archetype embodied by Jesus models a path of empathy and radical presence, urging us to do the same for others.

Yet, this nearness comes with a challenge: to let our lives be reshaped by his example. Jesus invites us to move beyond passive spectatorship and into active participation in the work of healing, justice, and reconciliation. The archetype of the saviour thus becomes a mirror, reflecting both our vulnerabilities and our potential.

Are we willing to let this closeness unsettle our routines and push us toward greater compassion? To reach out for a saviour who does not promise easy answers, but instead calls us to a braver, more generous way of living? In grappling with these questions, we discover that the true power of the saviour archetype lies not in distant heroics, but in the invitation to walk a more meaningful path, side by side.

The Healer Within

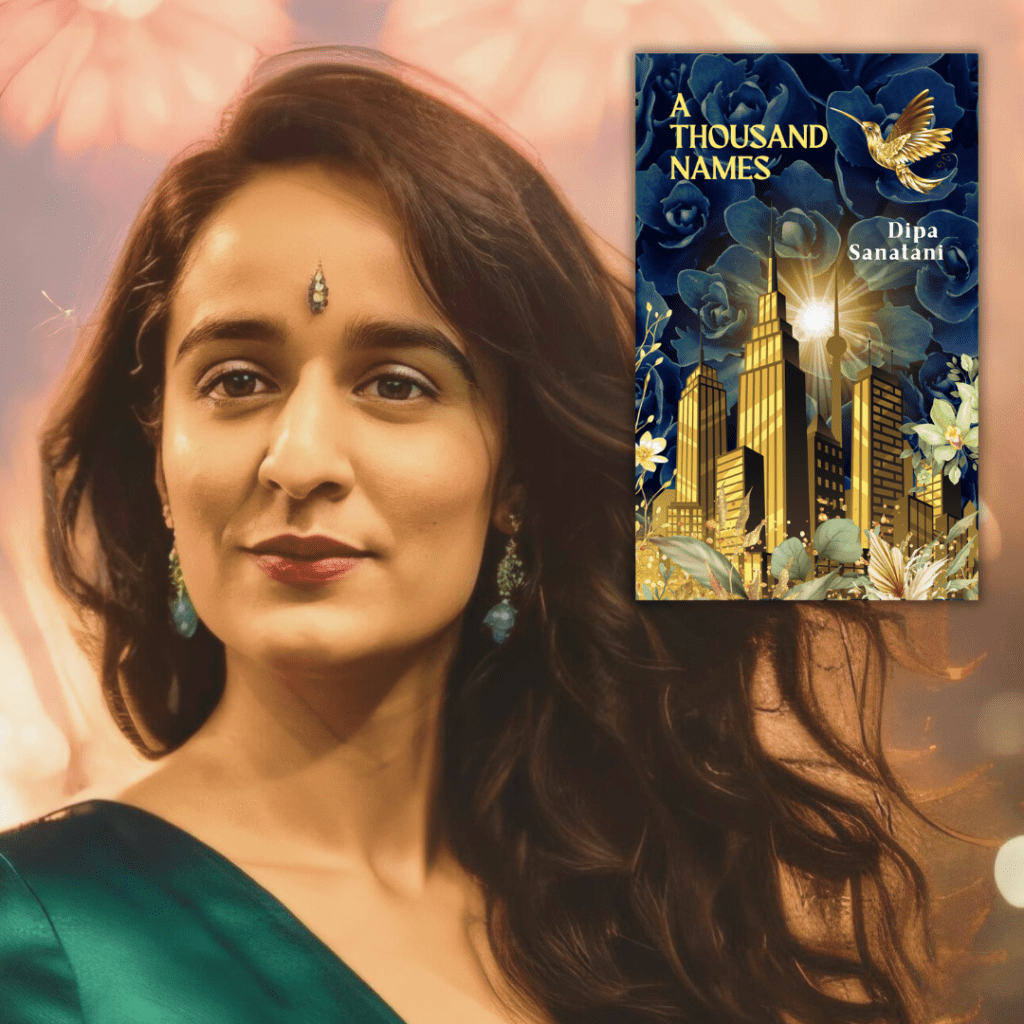

For readers drawn to stories of spiritual healing and symbolism, my novel A Thousand Names offers a thoughtful exploration of the search for meaning and renewal, especially for those interested in theology. Through the journeys of Jaya and Zadkiel-two oracles shaped by fate-the novel bridges Hindu and Christian traditions to reflect on trauma, resilience, and the quest to discover the Divinity within oneself.

Structured in 108 chapters to echo sacred tradition, A Thousand Names invites readers to move from the shadows of the past toward the light of the future. Available at all major online bookstores and at Singapore’s National Library Board (NLB) libraries, this novel is a moving testament to the healing power of introspection and spiritual awakening.

Leave a comment