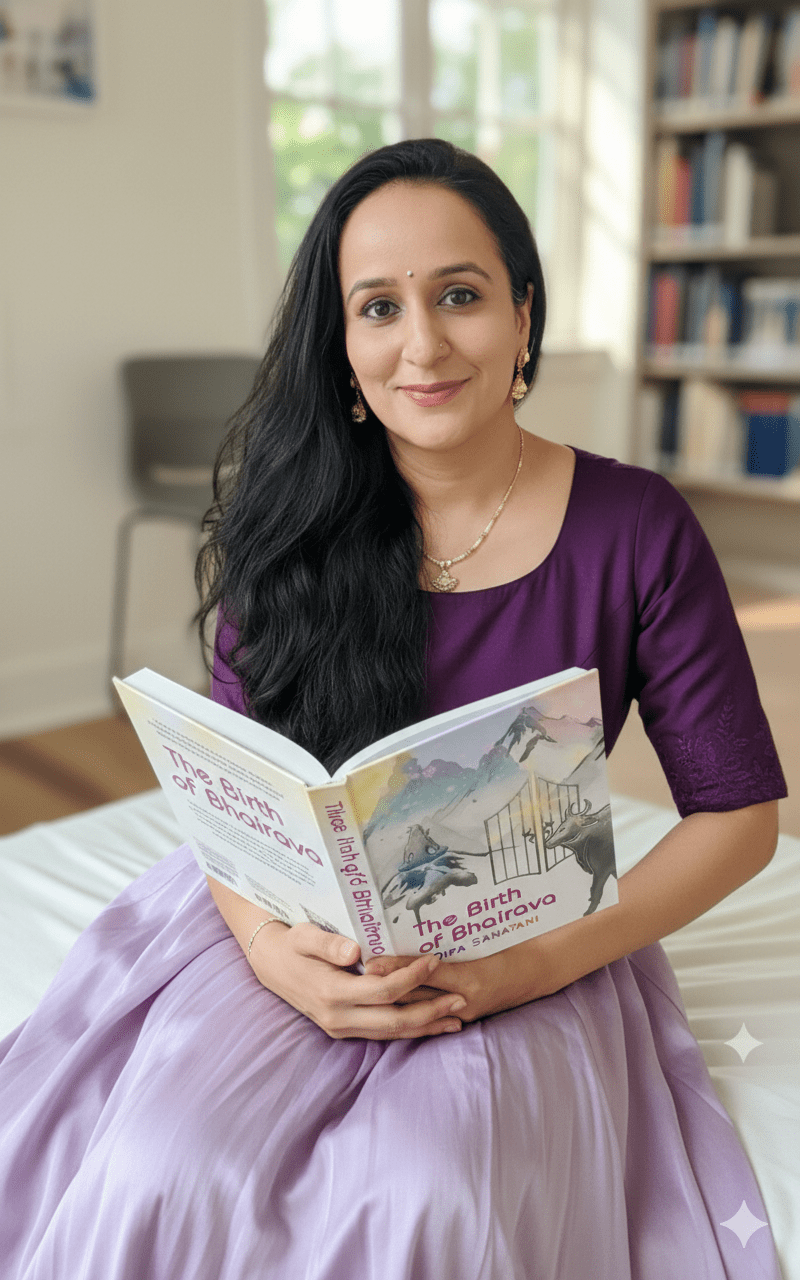

I am truly impressed with the way that Tagore’s female characters have been depicted in the Indian television series Stories by Rabindranath Tagore. They are, in many ways, similar to the women I knew growing up. Having grown up under the force of oppression, they had become oppressive themselves.

I have known many women who have grown up in conservative societies. Their capacity for cruelty was no different to any of the men. Yes, they were oppressed, but they are equally capable of doing the oppressing. Anyone who believes that women did not have a voice has neither heard the humiliating scorn of a Matriarch’s words nor the thud of her tight slap.

A few months back, I bemoaned to someone the lack of what I believed to be and would describe as accurate female representation, especially when it came to women from conservative societies. The conventional wisdom is that they needed to become more liberal. But it is hard to cast off the chains when that’s all you’ve known. When given the chance, they would simply choose to put those chains on someone else.

One area where I felt that Tagore played special attention to was the way in which women did exercise their authority, especially when their self-interests were at stake. Mothers who would show an incredible amount of love for their own children would be depicted as equally cruel to the children of other women’s.

There are, however, moments of compassion that surface midst all the cruelty. The shame they sometimes reveal through their eyes when they realise that they’ve taken their cruelty too far.

The characters are archetypal as opposed to stereotypical. The husband figure who never bothered to discuss or consult his wife on any matter before making a decision. The father figure who is never around but always busy with work. Men are both ‘there’ and ‘not there’.

One lingering and overarching theme that I saw in all of the stories is the deep unhappiness that marriage inevitably brings. Even though there’s the lovely jewellery, the red saree and the pomp-filled wedding, the relationship is almost always doomed. The bride looks sad at having to leave her home and move to her in-laws. The husband acts like it is business as usual. His obliviousness to his wife’s challenges is startling to behold as a viewer. It would shock you less if the reality were different.

People did not date or have the opportunity to get to know each other back then. Any intimate relationship, unless it was an extramarital one, necessitated marriage. The only people who had extramarital relationships were courtesans, entertainers and husbands who didn’t come home on time and said they were busy with work.

Meetings and conversations between parties interested in one another had to be done secretly, slyly, cleverly and coyly. For women, the transition into marriage was a transformative one, but not for the men. A woman would outwardly change. She would now wear the sindoor and the mangalasutra. Her environment, of course, would also be altered. She would move in with her in-laws and with that, her destiny would change as well.

Love and attraction never factored into why two people got married. For the most part, it was something separate to the act of getting married. You had to marry the person who suited you or the person you were making a commitment to. You weren’t actually allowed to choose your partner. At the same time, forced marriages were rare. There were a list of suitable and potential candidates and you would have to choose from that list.

You would meet the person a few times and if everything was agreeable, the two would marry. And then, one would quickly realise that it was all doomed from the start. Problems would surface, secrets would surface and the marriage–despite all the pomp and grandeur of the wedding–would be a complete and utter failure.

Leave a comment